“Never doubt that

a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world;

indeed it’s the only thing that ever has”

-Margaret Mead

Getting FASD in the DSM: The Work of a

Few Good Doctors

by Kathleen Mitchell

Over time, I have come to the conclusion that more specifically

diagnosing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) is key to both

prevention and treatment. This is based upon my own experiences

and observations in the professional world.

The day my daughter, Karli, was diagnosed with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

(FAS) I knew that my life had changed forever. For 15 years I had

searched to understand why she was not learning and growing stronger

like my two other children. The most common misconception that I

encountered was that Karli was going to “grow out of it.”

Physicians told me that her developmental disabilities were a result

of suffering from chronic ear infections. “Give it some time,

children are very resilient to these types of delays; she’ll

be fine,” was the message I heard over and over again.

Karli is now 32 years old. She never did grow out of it.

Once she was correctly diagnosed with FAS and I understood that

Karli’s disabilities were a direct cause of my drinking during

pregnancy, it catapulted me into advocacy. I had not known that

alcohol could cause harm to my unborn child. I knew then I had to

tell others of what had happened to Karli. I jumped in with both

feet, and shared our story with all who would listen to educate

other women. This was to become my destiny; if I could prevent one

alcohol exposed birth, then my time was well spent.

During my advocacy efforts, I met Susan Rich, who shared a similar

passion for FASD prevention. Since then, she has become a child

psychiatrist and is currently completing a two-year fellowship at

Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C. Along

with Dr. Roger Peele, an American Psychiatric Association (APA)

trustee, she recently wrote and submitted an action paper that advocates

that APA explore having FASD included in DSM-IV-CR / DSM V (Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Book IV Content Revision

and Book V, respectively) and subsequent editions of the manual.

Dr. Kieran O'Malley of the University of Washington's Fetal Alcohol

and Drug Unit offered invaluable assistance and guidance for her

paper. I was delighted to be included in that process. We also had

brilliant input from Adam Litle, our past Director of Public Policy

at the National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (NOFAS).

The paper was quite a success! It received a unanimous endorsement

from the Washington Psychiatric Society Board of Directors, as well

as from the Mid-Atlantic States, the APA, the American Academy on

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry's Assembly, the Area Committee on

Members-in-Training, and the APA's Assembly (at their annual meeting

in May 2005).

The importance of having a psychiatric code for FASD from infancy

to adulthood has been discussed for years. This code will open the

doors for early intervention. Currently there is no way for psychiatrists

to diagnose FASD, although they are typically the ones who treat

individuals with FASD. The majority of individuals with FASD do

not have mental retardation, but may have numerous behavioral, mental

and/or psychiatric issues that place them in the care of psychiatrists.

Psychiatrists will treat them based on symptoms and behaviors, even

when they suspect the issues are related to prenatal alcohol exposure.

Pediatric dysmorphologists typically are the medical professionals

that diagnose FAS, but may not identify other disorders associated

with prenatal alcohol exposure such as Alcohol Related Neurodevelopmental

Disorder (ARND). As well, the dysmorphologists form their diagnosis

based on the transitory appearance, from ages 6 to 12 years, of

the classic FAS facial dysmorphology. Some physicians report that

they are reluctant to diagnosis FAS because there are really no

treatments or services available, so they prefer not to “label”

children.

Obviously, failure to identify and diagnose these disorders results

in underreporting of FASD. Most health care professionals and institutions

are greatly ill informed on this issue and view it as a “rare

disorder.” NOFAS estimates that 40,000 (or 1 in 100 infants)

are born with some type of preventable damage from prenatal exposure

to alcohol. That is a population larger than those with Down syndrome,

cerebral palsy, and spina bifida combined.

There are many benefits that would naturally result from inclusion

of FASD in the DSM:

- Increased awareness of FASD among those that work in the mental

health field, such as psychiatrists, psychologists, therapists

and counselors.

- Increased global awareness of FASD in all healthcare and human

services systems of care.

- Better accuracy in the actual numbers of FASD cases treated.

- Increased motivation to intervene and treat women with addictive

disorders.

- Increased efforts to prevent FASD.

- Enhanced services for individuals with FASD.

- Increased knowledge of pharmacological and other interventions

that are successful for individuals with FASD.

Having a DSM code for FASD may result in a domino effect. The

more cases that are identified, the more healthcare professionals

would become aware of the disorders, and then the more likely they

are to understand the importance of prevention.

Certainly, individuals with FASD and their families are receiving

services; they are in our systems of care. The question becomes:

Are they receiving the correct services? As most individuals are

undiagnosed or misdiagnosed, unfortunately, the answer becomes:

Probably not. Those administering of our systems of care just do

not know what they do not know!

This is such an important advocacy effort that this committed

group of physicians has taken on. I honor Dr. Rich for her commitment

to making a difference in preventing FASD, Dr. Peele for his support

and enthusiasm, Dr. O’Malley for his brilliance, expertise

and desire to help those with FASD, and NOFAS members for having

the insight to understand the importance of supporting this effort.

As always, this is a personal effort for me, as I see it as a way

to help other families struggling to help their children.

Kathleen Mitchell is the vice president and national

spokesperson for the National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

(NOFAS).

| Your voice

is important!

You can help this effort to include FASD in the DSM by contacting

your local Psychiatric Association, and by sending a letter

to the president of the American Psychiatric Association expressing

support for inclusion of FASD in the DSM. Dr. Susan Rich is

compiling personal stories and letters from families, researchers

and advocates to share with the committee that will be studying

the issue. If you are interested in contributing, please write

a description of the mental health issues and challenges your

family member has experienced, along with the tribulations

of not having an accurate diagnosis, and email it to Dr. Rich

at srich@cnmc.org. Please use “FASD in the DSM”

in the email’s subject heading.

|

return to top

Prenatal Alcohol Exposure Research in the

early 1900s

by Katy Jo Fox

The discovery:

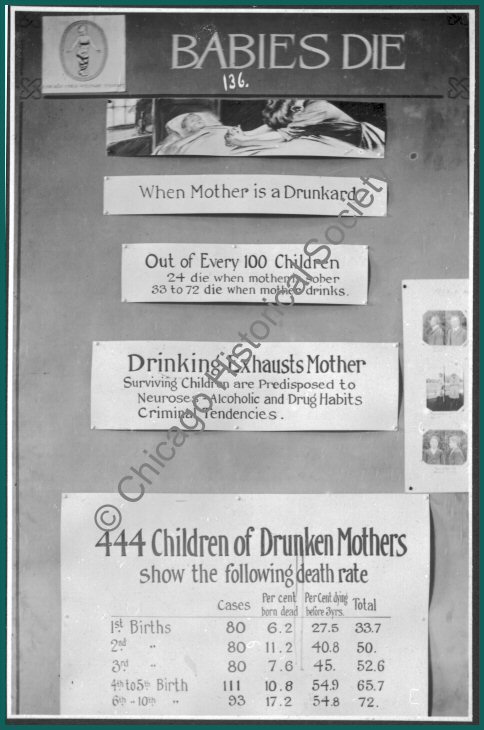

I have been a member of FASlink (a ListServ for issues relating

to Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders) for eight years now, and every

once in a while something will be posted that completely astounds

me. This past January was one of those times. A wonderful Canadian

gal named Claudia, doing online research into women's drinking habits

pre-1950, stumbled upon a book with a most interesting photo (see

below) introducing one of the chapters. She sent the link over FASlink

so that we too could see it.

Babies Die exhibit: The Chicago Child

Welfare Exhibit; 1911. Photographer unknown.

Courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society.

My quest:

I had to know more about this photo. The credits were given to

the Chicago Historical Society (CHS), so that is where I started.

I emailed them asking for more information. While I waited for a

reply, I slowly enlarged the picture so I could somewhat make out

the first three of the four words under the logo in the upper left-hand

corner: Chicago Child Welfare. I went to Google.com to search for

that organization. The results delivered that final word: Exhibit.

I started surfing through the links and found a book titled "The

Child in the City; a Series of Papers Presented at the Conferences

Held During the Chicago Child Welfare Exhibit." Harvard had

a scanned copy of this book online, and I was thrilled to see the

logo on its front page. Some rather historical figures stood out

in the table of contents, including Jane Addams and Booker T. Washington.

Unfortunately, there was no mention of alcohol and mothers who drink

in this book. Another link told me a bit more about this exhibition—a

quarter million people attended, more than an eighth of Chicago's

population at that time.

I emailed CHS, told them what I had found, and asked for confirmation

that this photo was from the Chicago Child Welfare Exhibit. CHS

confirmed that it was, and that it is now part of a collection of

photos the society has from the exhibit. They did not know any more

about it, but did say that the exhibition took place May 11-12,

1911. They did some research and found a page showing entries for

the exhibition in the Chicago Record Herald, and mailed

me a copy of that page. Unfortunately, the clipping did not help

my quest. A few weeks later, a larger, scanned version of the picture

arrived from CHS. I enlarged it further, but was unable to read

the small writing below the three pictures on the left. However,

I could see that the first part of the word on top of those pictures

read “Feeble-M," and that the pictures were not taken

at a jail (although they looked like mug shots).

I kept searching for other angles on Google. I started at the beginning,

the online book I found the picture in, titled: “The First

Measured Century.” It is a reference volume for a 3-hour PBS

special of the same name. As I searched for the exact site, I came

across a transcript of a discussion on "Infant and Maternal

Mortality: How Julia Lathrop and the Children's Bureau Tried to

Save the Babies." Unfortunately, the Children's Bureau was

established in 1912, following the exhibit. A search on Julia Lathrop

herself amazed me. Julia lived at Hull House with Jane Addams, and

one of her jobs involved visiting over 102 almshouses, farms and

settlements in and around Chicago that collectively housed the mentally

ill, aged, sick and/or disabled. She also helped found the first

juvenile court in the United States in 1899, and even established

a psychiatric clinic for young offenders. Julia wanted to prove

that mental illness was not a sign of moral defect, a belief that

was counter to common opinion, even among those in the medical field.

Later in life, she focused her work on combating infant mortality.

Here was a wonderful woman who did all kinds of statistical research,

whose CV would have been just as long or longer than Ann Streissguth's,

FASD’s pioneering researcher, and who had all the qualifications

needed to do the kind of research seen on this picture. More importantly

for my quest, she had been doing research prior to 1911.

In my hunt for information on Julia Lathrop I came across an article

by Dr. Patrick Curtis titled, “The Beginnings of Child Welfare

Research in the United States.” It compared Julia’s

belief about the cause of mental illness to those following a different

path, specifically, eugenic reformers. They believed that so-called

moral defects, like drunkenness, were passed down to their children,

in the form of “feeble-mindedness” and delinquent behavior.

I had a hard time explaining to someone the difference between this

belief and Julia’s, especially when applied to drinking during

pregnancy, since alcohol was the teratogen that caused the damage,

and the mother was the person who actively drank it. I developed

this hypothetical scenario as a way of explanation: Say female subject

A was a “loose woman,” — definitely a moral defect

for this time period. She got pregnant and had a baby girl who,

later in life, turned to prostitution and crime. Was this just a

reflection of her environment, or was this because she was predisposed

to moral defect? Would it make a difference knowing she was prenatally

exposed to alcohol? Today we have the ability to scientifically

go out of the box. We know what alcohol does to the brain, causing

people prenatally exposed to it to be more vulnerable and making

them easy targets to the whims of criminals. Bless Julia Lathrop

for believing in something that could not then be proven!

Another source of information about the Chicago Child Welfare Exhibit

was “Childhood and Child Welfare in the Progressive Era,”

by James Marten, which had several chapters about the exhibit and

highlighted the work of Julia Lathrop. Unfortunately, the book contained

no clues about the research presented on the exhibit poster. However,

it did cite a booklet titled “The Child in the City: A Handbook

of the Child Welfare Exhibit at the Coliseum, May 11 to May 25,

1911,” published in 1911 by Blakely Printing Co. in Chicago.

Although Google could not help me track down this publication, I

was able to find and email James Marten, who told me that it was

available through Interlibrary Loan. I was quite excited when, a

few weeks later, the handbook was available at the library. Skimming

through it, I looked carefully through the names of various speakers

and committee members. No mention of Julia Lathrop. I then skimmed

through the various descriptions of demonstrations, everything from

Chicago’s Open Air School, which turned “sick school

children into stout and clever ones,” to how to sterilize

baby bottles. The descriptions were quite vivid. The previous year,

3,500 children died in Chicago from preventable diseases. One display

had a line of dolls, where every fourth doll dropped into a grave--only

three in four infants grew up. Every aspect of the child’s

life was examined, and recommendations aired.

I started to read the section titled “Eugenics,” and

by the end I knew I had found the source for this picture. It discussed

the need to scientifically look at mental and physical disabilities,

and asserted that many of these disabilities could be prevented

and that “the responsibility for these ills rests with the

parent, the community, and the state…the policy of silence

and suppression of information must be abandoned…that condemnation

and prohibition must give place to education.”

I was happy to see that it looked like the theory of eugenics was

in for a paradigm shift. Alas, it was too much to hope for. They

were only at the beginning stages of this shift. Instead of using

their knowledge to warn women about the dangers of drinking during

pregnancy, they clung to their cloak of supremacy in breeding. As

much as this quote sickens me, I have to share the last paragraph

of this section, as it completes my quest:

“Infant mortality as a result of early marriages, strong

drink, overwork and work in certain industries—the manufacturing

of lead products, for example—are shown by statistics. The

ravages of diseases are similarly set forth. A strong argument

for preventing the mating of the unfit is made by chart and photograph

illustrating the heredity of feeble-mindedness.”

Thoughts on "what went wrong":

If Iceberg readers are like me, they might be wondering why these

statistics are in archive form only. Regardless of the researchers’

personal beliefs, if they knew without a doubt that babies died

when their mothers drank (remember, there were then no resources

for keeping failure-to-thrive babies alive), and they knew that

those babies who did survive childhood grew up to have Neuroses

(depression), drug and alcohol habits, and criminal tendencies,

why was this research buried and forgotten? Perhaps it is because

with the invention of immunizations, fewer babies were dying. Perhaps

with WWI and then the Great Depression, people had other concerns

and it was slowly forgotten. Perhaps it is because the alcohol industry

found a way to suppress this information, or maybe even society

itself was in denial that a once again legal drink could have such

a harmful effect on offspring.

Interestingly enough, this question is one of the main topics in

a 2003 book titled “Conceiving Risk, Bearing Responsibility,”

by Elizabeth M. Armstrong (for those looking for a good book on

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders, I absolutely do not recommend

this book). Ms. Armstrong has a number of misguided notions (such

as Fetal Alcohol Effects being a lesser form of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome)

and the more I read her book, the more frustrated I became at her

lack of accurate and updated research, which was reflected in her

conclusion that FAS was more a diagnosis of the birth mom than brain

damage that may not even be noticed (without brain imaging, which

she also had a problem with) until adolescence. However, the first

part of this book does have an excellent historical analysis, from

Plato to the present, for those interested in the changing thought

process on the visible effects of alcohol on offspring. Again, her

ideas that these were not really a historical analysis on prenatal

alcohol exposure, more a refection on morality, may not be totally

accurate.

One bit of research mentioned in Ms. Armstrong’s book was

a study done in a Liverpool prison where William Sullivan studied

siblings of alcoholic mothers. He found that the children the mother

carried in prison, without access to alcohol, fared better than

their siblings carried out of prison. Morality could not have been

an issue in this study as the children all came from alcoholic mothers

who at one time or another spent time in prison.

Going back to the issue why this information was lost, Ms. Armstrong

does ask the question of why the research of many doctors from around

the world involving alcohol in pregnancy seemed to disappear. Her

thoughts are that, in the age of medicine and scientific research,

doctors thought that the studies of the past were not based on accurate

research. Also, after WWII, most doctors in the U.S. did not want

to accept any past research based on concepts of morality or the

supremacy of offspring. It is quite possible that she is correct,

as all other countries that had researched alcohol and pregnancy

were directly affected by Hitler’s ideology.

There are many other questions one can ask when looking into the

past. Did the research presented on the poster generate any prevention

campaigns? In Ms. Armstrong’s book there is a poster from

a 1909 anti-saloon billboard that asserts one can’t drink

liquor and have strong babies. The language in the rest of that

billboard is pretty strong and probably was viewed as more irrelevant

ranting from groups determined to close down all sources of alcohol,

rather than accurate scientific research. Was the research in this

poster seen as irrelevant ranting from people determined to better

the gene pool? We may never know the impact this poster had on those

who saw it. We may never know how far these eugenic reformers took

their research and conclusions. We may never know who exactly funded

this research and who carried it out (for those interested, the

handbook did list the names of people in the sub-committee on eugenics

for the Chicago Child Welfare Exhibit ). We can only say thank you

to those who rediscovered the harmful effects of drinking during

pregnancy – Dr. Paul Lemoine and Dr. Ken Jones (and be glad

that they did not attribute it to moral defect) – and thank

you to all who have devoted their lives to researching, diagnosing

and working with those who have Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders,

as well as everyone working towards prevention.

Katy Jo

Fox is the Web master and office assistant for the Fetal Alcohol

and Drug Unit at the University of Washington in Seattle, and an

Iceberg board member.

return to top

Response to "Getting FASD in the DSM:

The Work of a Few Good Doctors"

by Charles Huffine

It was a pleasure to read Ms. Mitchell’s article and realize

once again the power of parent advocacy. I, too, have labored for

reform in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders

(DSM) and have come to realize how slow and conservative the American

Psychiatric Association is in allowing change. My position is slightly

different than Ms. Mitchell’s.

We need to keep in mind that a psychiatric diagnosis accompanying

a medical problem needs to be separated out for inclusion in the

DSM. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) would never be considered

a psychiatric diagnosis per se, only the brain functioning part

of that diagnosis and not the dysmorphology. I would advocate for

Alcohol-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorders (ARND) to be the psychiatric

diagnosis. Interestingly there is a possible code for ARND buried

deep in the schedule of diagnoses: DSM IV, Axis I, 310.1 Personality

Change Secondary to (X Medical Condition). The text of the DSM specifically

says that the personality change can be the difference of what the

child’s personality might have been had the child not had

damage in-utero. The medical condition is Fetal Alcohol Exposure.

This is a confusing and underused diagnosis. I have found very

few who use it even in my community where I have been advocating

for its use for many years. ARND would be a much more specific diagnosis

and would challenge the FASD community to carefully define it with

criteria that distinguishes it as a distinct diagnosis. I would

code it next to Personality Change Secondary to (X medical condition)

as 310.2.

I have earlier written for Iceberg on the importance of having

the psychiatric issues of FASD specified in the DSM as a means of

helping psychiatrists avoid throwing them into the amorphous and

much-maligned pool of Conduct Disorder and the other Disruptive

Behavior Disorders. (Huffine, C. “It’s Time Psychiatry’s

Diagnostic “Bible” Addresses FAS, Iceberg June 2000.)

I hope, in time, that this will be the case.

Charles

Huffine has practiced child and adolescent psychiatry in Seattle,

Washington since 1975. He is currently in private practice and is

the Assistant Medical Director for Child and Adolescent Services

at the King County Mental Health, Chemical Abuse and Dependency

Services Division.

return to top

What You Can Do to Support Students with

FASD

by Wendy Olson

I am a Special Education Teacher, and when asked to comment on

how to teach kids with disabilities, I often wonder what would be

helpful to others there in the trenches. Working with children who

are affected by Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) is tough.

Period. There are days when I can feel like I get little return

for my investment, as progress takes time, determination and a lot

of repetition.

Then I think of my students and how we really do have little victories

every day. Just this week, we celebrated a first 100 percent spelling

test taken by one of our students who is Fetal Alcohol Effected

(FAE). There are small and often unrecognized signs of progress.

After reminding a child with ADHD not to climb on the counters (again),

she looked up, smiled sweetly and declared fervently, “I will

learn it!” My students often humble me with their positive

outlook.

I’m a pragmatic individual. I don’t spend a lot of

time belaboring theory. Much of what I have learned comes from good,

old-fashioned trial and error. Research is important, so long as

you use it to inform your practice. In other words, what interests

me is what I can do to help my students today. What follows are

the ways I try to position my students for success.

Providing structure

I arrange my classroom with the specific needs of my student population

in mind. There should be no clutter; I avoid hanging anything from

the ceiling, and only gradually introduce the idea of displaying

student work on the back walls (usually not before January).

I break the room into areas, each with a specific function and

all visually separate from the rest of the room. For example, large

tables for group work are sectioned into individual spaces using

colorful electrical tape, which is necessary when working with children

who struggle with knowing where they are in space and therefore

tend to encroach upon others.

My students also often have problems with sensory integration,

and may be sensitive to visual, auditory or tactile input. We try

to keep the noise level down whenever possible. Turning off a few

lights and playing soft music can really help. In the past, I have

provided particularly sensitive children with construction headphones

to block out sound. But some students need input, so such a child

can hold a Koosh ball while listening to a group lesson (keeps those

busy hands from peeling the nametags off desks). Giving directions

in sign language while speaking them can give additional helpful

input to children with auditory processing issues.

When properly supported in a structured environment, even the most

profoundly affected children can learn appropriate school behaviors.

Visitors have commented that I have the best-behaved classroom in

our primary unit. When asked about what I use for a behavior management

system, I always answer, “structure.”

Structure can be applied to any activity, while allowing for choice

and freedom. When I first tried a free-choice math activity period,

we had nothing short of chaos, even though I had carefully outlined

which activities were available. So I tried upping the level of

structure by laying out each activity in a different area and placing

carpet squares where students could choose to be.

Now, before we begin an activity like this, I stop at each area,

show the activity, and ask students how many children may be in

that area. By looking at the carpet squares, they know if two or

four may play. With the simple addition of visual structure (carpet

squares), they are able to choose an activity and manage themselves

with a fair degree of independence.

Focus on the positive

While structure is key, positive behavioral management is critical.

Simply stated, you focus on the good stuff and try to give minimal

attention to the bad stuff (unless safety is an issue, of course).

The problem comes when we insist upon delivering a punishment (often

not even a natural consequence), thereby putting our attention in

the wrong direction.

It is important that we as educators remember that behavior serves

a purpose: it is communication. Before you try to stamp out a behavior,

step back and ask yourself: “Why is my student doing this?

What is the purpose?” You’ll need to teach an appropriate

replacement behavior that gets the child what he or she needs if

you wish to extinguish a problem behavior.

When thinking of recognizing the positives, praise is not enough.

There should be a reward system in place. After all, we all expect

a paycheck when we go to work and school is a child’s work.

In the best of all possible worlds, feedback is immediate and tangible.

In my room, I use classroom money that an old friend designed for

me. Our Buckaroonies are given out for hard work, good behavior

and kindness towards others. Throughout the day, my paraeducators

and I give out money to students who are on task. Children who are

not working are skipped over without comment, as we quietly tell

the other children, “Thanks for your hard work.” It

is amazing how quickly that off-task student will pick up his pencil

and get busy.

Hands-on, real life experiences are critical for children with

FASD. Students in my classroom are expected to manage their own

money. They earn additional funds by doing classroom jobs, and are

paid for these by check on the first and third Fridays of the month.

Every Friday, we have “Store” instead of math. I expect

students to sort out their cash by denomination, count it and decide

whether or not to cash their paychecks, which must be endorsed.

The store is actually a rolling set of plastic drawers with items

arranged by price. Students may purchase books, school supplies

or educational toys with the money they have earned. This is a good

opportunity to practice social skills, as children are often upset

when they can’t afford an item or someone else buys what they

had hoped to have for themselves.

Engage the students in their own education

When children are supported properly with the right degree of

structure and positive behavior management, they are ready to be

active participants in their own learning. I make a point of talking

to them about IEPs (Individual Education Plans). Whether my students

can read or not, I show them the goals that their parents and I

agreed we would work on this year. We talk about individual progress,

and familiarize them with the data sheets in their binders.

Often times, students participate in data collection by counting

the number of flashcards they read correctly, or helping to calculate

a percentage by punching numbers into a calculator (with some assistance).

I ask them to look at their scores and tell me if they did better

than yesterday. When an IEP objective is met, my students receive

a certificate to take home and get congratulations from their peers.

Educating children with FASD is a challenge, but it is also a gift;

I learn so much from my students! When structure and positive behavioral

support are provided and students are actively engaged in their

own learning, I like to think they learn from me, too.

Wendy Sunderland Olson is a Special Education Teacher

working for the Edmonds School District near Seattle, Washington.

She has a B.A. in special education and a M.Ed. in severe disabilities.

Previous to teaching, Mrs. Olson worked as a research coordinator

for the Fetal Alcohol and Drug Unit at the University of Washington.

She is currently in her fifth year of teaching in a self-contained

special education classroom serving children with FASD, Autism Spectrum

Disorders, developmental delays, and health impairments.

|